As the saying goes, curiosity killed the cat, but that paints curiosity in a bad light. Sometimes curiosity is a good thing, as with a recent "Let's see what happens" moment at the University of Alabama that could revolutionize plastics recycling. According to the Alabama News Center, that's exactly what led a team of researchers to discover a better and more efficient method of breaking down recycled plastic.

The plastic pollution problem across the globe is almost too big to fathom. There are hundreds of trillions of pieces of plastic floating in the world's oceans, and that's not even counting all the plastic in other waterways or slowly deteriorating in landfills, or the microplastics found in our own bodies.

Then there's the problem with recycling. For starters, less than 10% of plastics in the United States are recycled. With the little plastic that is recycled, the processes for breaking it down produce lower-quality plastics with less value and fewer uses.

These processes generally use amines, compounds derived from ammonia that are useful in breaking down polyethylene terephthalate, a common plastic used for all sorts of things, including water bottles.

Jason Bara, a professor in the College of Engineering, had been working with amines for a couple of years to break down plastics as part of a National Science Foundation grant for the purpose of reducing plastic waste. But he decided to try something new — just to see what happened.

"I've been working with imidazole for much of my career," Bara said. "It's pretty amazing how versatile it is."

Imidazole is a compound used in pharmaceuticals, textiles, paints, printing, and a whole lot of other things. So, Bara figured why not see how it does breaking down plastic?

He described the moment he found out the results, saying: "My student came back into the lab and said, 'Oh — the plastic is gone. It's all gone.'"

Breaking down PET using imidazole produced compounds with a wider range of uses than those of the current processes, and it appears to be more cost efficient and commercially viable, all of which will ideally lead to less plastic waste.

🗣️ Do you think America has a plastic waste problem?

🔘 Definitely 👍

🔘 Only in some areas 🫤

🔘 Not really 👎

🔘 I'm not sure 🤷

🗳️ Click your choice to see results and speak your mind

But Bara isn't stopping with PET. He's set his sights on polyurethane, which you might find in your couch cushions or packing foam. Though biodegradable PU might be just around the corner, it's not a thing yet. The countless tons of PU on the planet adds to the plastic waste problems mentioned above.

Bara says that imidazole also works in breaking down PU into recoverable and reusable molecular components and may have a "much bigger impact" on the efforts to curb plastic waste.

The university is going through the patent process for this new technology, but it sounds like a promising step in the right direction.

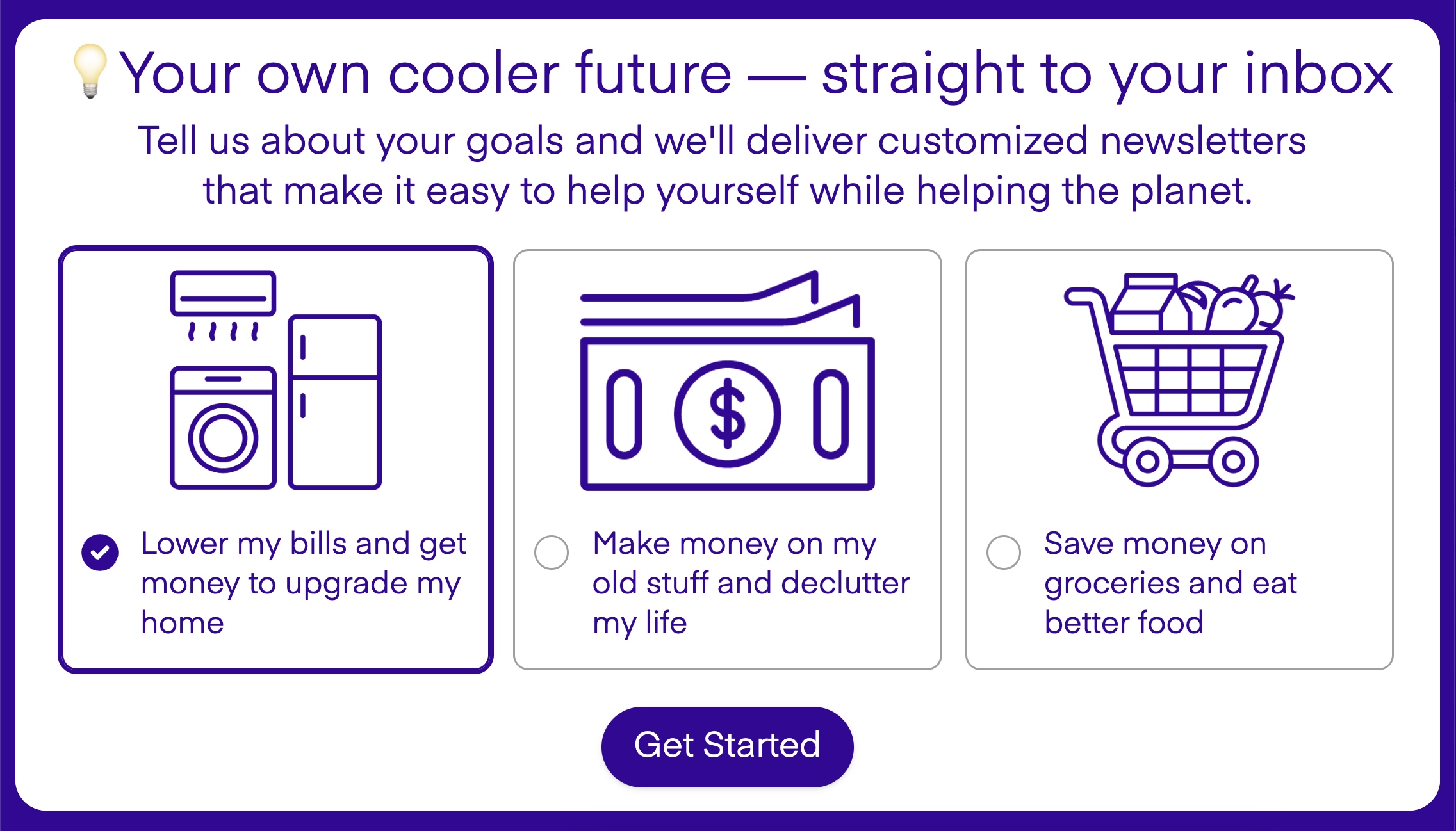

Join our free newsletter for weekly updates on the latest innovations improving our lives and shaping our future, and don't miss this cool list of easy ways to help yourself while helping the planet.