A team of scientists from South Korea is working to lower the cost and boost the durability of promising proton exchange membrane fuel cells by doping expensive platinum-cobalt catalysts with nitrogen.

Experts from the Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology outlined the strategy in a news release. The goal is to commercialize hydrogen fuel cells for wider use. They are touted by many energy experts as a prime alternative to dirty fuels such as coal and natural gas. That's because hydrogen produces electricity, water, and heat — not harmful, planet-warming air pollution — when used in a cell, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

"Our research focused on addressing the durability limitations of existing alloys to significantly enhance fuel cell performance," professor Jongsung Yu said in the news release.

Proton exchange membrane cells include an anode, a cathode, and the proton exchange membrane. A typical platinum catalyst works to split the hydrogen into protons and electrons. The membrane filters out the electrons, which can be used to generate electricity to power vehicles and other machines. The protons are used in a reaction that generates water as part of harmless byproducts, all per a description from New York's Plug Power, a hydrogen fuel cell developer not involved with the DGIST research.

Platinum is expensive, at about $964 per metric ton, according to data collector Statista. Platinum-cobalt catalysts also suffer from low durability. But the DGIST report outlined how adding nitrogen to the material improved it. The nitrogen bonds with the cobalt, stabilizing the metal. The technique also reduces the amount of expensive platinum needed.

"By advancing the application of platinum-cobalt alloys with outstanding initial performance to practical fuel cells, we have developed a technology that meets the demands of both longevity and efficiency for hydrogen fuel cells," Yu said in the lab report, which added that the material has met key DOE "durability targets."

For its part, hydrogen isn't without some dirty baggage. Most commercial hydrogen in the United States is made with a process that uses dirty fuels. When combusted, hydrogen emits nitrogen oxides, which can be harmful when inhaled, according to U.S. government reports and a fact sheet from environmental watchdog the Sierra Club.

Hydrogen made with renewable electricity through electrolysis, and then used in a fuel cell, is the cleanest production-to-use path described in the reports. It's an example of converting intermittent renewable solar energy into stored chemical energy for later use.

And innovators around the world are developing amazing machines, from aircraft to ships, that can be powered by the gas. A novel high-speed train recently debuted in China, for example.

|

Should we be digging into the ground to find new energy sources?

Click your choice to see results and speak your mind. |

Since hydrogen's energy content by volume is low, it must be stored at high pressure, another setback, the DOE noted. But eliminating planet-warming fume production is an alluring perk driving big investments. Curbing the pollution is important to limit the worst-case impacts of the world's overheating, which is being felt in our oceans and food chain.

Some simple moves at home can contribute to cooling things down. Upgrading to LEDs from light bulbs can save you hundreds of bucks a year in power costs. LEDs are five times more efficient than traditional illuminators, cutting pollution output significantly.

At DGIST, the researchers hope their doping findings have a great impact across multiple industries.

"We hope this achievement will contribute to making hydrogen fuel cells a sustainable energy solution across various applications, including automotive, marine, aviation, and power generation sectors," Yu said in the summary.

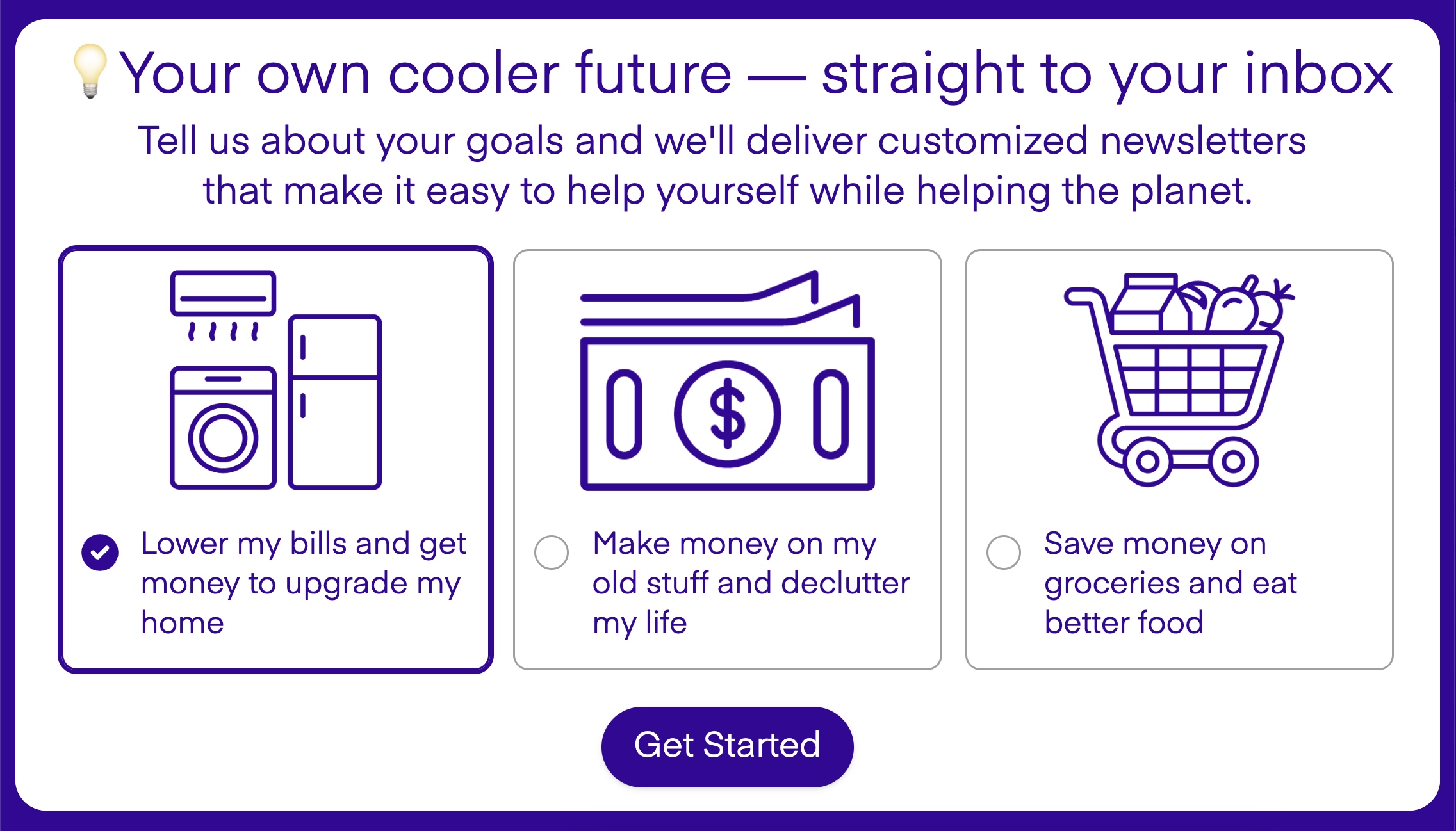

Join our free newsletter for weekly updates on the latest innovations improving our lives and shaping our future, and don't miss this cool list of easy ways to help yourself while helping the planet.